Our Proud History

INDIANA UNIVERSITY

ARMY ROTC

The history of military training at Indiana University is almost as old as the University itself.

“The power of noble deeds is to be preserved and passed on to the future.”

JOSHUA LAWRENCE CHAMBERLAIN

1816-1824

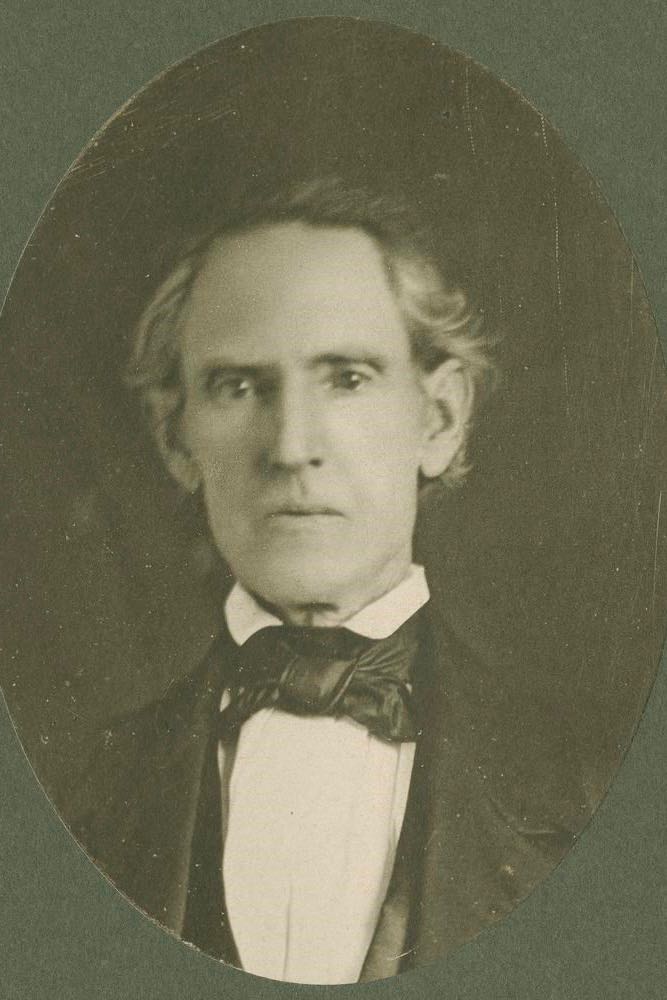

David H. Maxwell, the Founding Father of Indiana University, was the son of a Revolutionary War veteran and was himself a veteran of the War of 1812. Dr. Maxwell served as a surgeon with a company of Indiana Rangers. That company was lead by his brother-in-law, Williamson Dunn.

In 1816, Dr. Maxwell, while serving as a representative at the state constitutional convention, wrote IU into the state constitution. In 1820, the first Board of Trustees were selected and Bloomington was chosen as the site for the institution.

Dr. Maxwell was elected President of the Board; a position he would hold for 30 of the next 32 years. To keep an eye on his beloved institution, Dr. Maxwell moved his family to Bloomington as did his brother-in-law Samuel Dunn.

Eventually, after the fire of 1883 destroyed much of the Seminary Square campus, Samuel Dunn’s grandson, Moses Dunn, would sell part of his farm to the university and it would move to it’s current location, known as Dunn’s Woods.

The Dunn family’s military service was already well known and dated back to the Revolutionary Army. By the Civil War, so many Dunns had served in the military that the family became known as “The Fighting Dunns.”

Dunn Cemetery, located next to the Indiana Memorial Union, has several veterans buried in it dating back to the Revolutionary War.

1840-1843

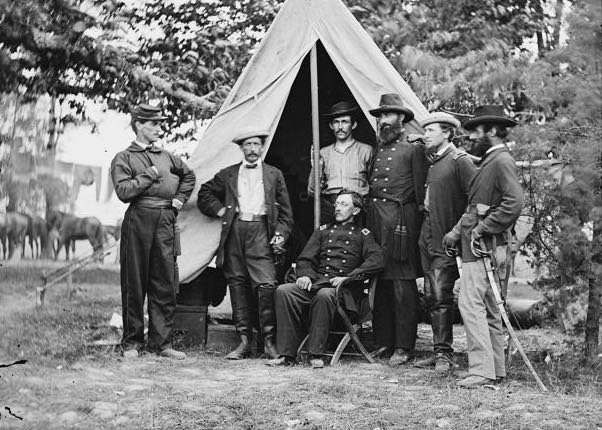

In 1839, the Trustees hired Jacob Ammen as Professor of Mathematics. Ammen had been educated at the US Military Academy at West Point and had served for six years in the US Army.

Before arriving on campus, Professor Ammen was asked if he would also teach a course on Military Science. By doing so, Indiana University became only the fourth collegiate- level institution in the country to offer such a course and the first non-military academy. The course was also optional, but once enrolled, students had to remain in it for the semester. This made it the first free elective course.

In 1843, due to severe budget cuts, Professor Ammen was hired away by another institution. His replacement taught only mathematics.

Professor Ammen would go on to serve in the Union Army during the Civil War and rise to the rank of Brigadier General. The IUB Army ROTC Cannon “Big Jake” is named after him.

1861-1865

During the Civil War, IU experienced a resurgence in interest in military instruction but had few options for formal integration into the curriculum. The university was just over a hundred and fifty students at that time. Out of the student body, there was a group known as the University Cadets, a company formed specifically for military tactics training. It is unclear who was responsible for leading the training. It may have been former soldiers recruited from among the local community. Their training seems to have been limited solely to tactics.

“As appropriate physical exercise is essential to health, and some knowledge of military tactics is not only desirable, but necessary for the complete education of young men, the students of the University have the opportunity of regular Military Drill, under competent instructors, in a company composed of students, called the UNIVERSITY CADETS.” (Annual Report of 1860-1861)

The formation and necessity of this unit had three motivations. First, IU students were not exempt from being drafted into the Union Army. Second, it limited the flow of students running off to join the Army. And thirdly, the Copperhead (Southern sympathizer) presence was strong in Southern Indiana so “home guard” units were needed. Copperheads were even on campus.

Shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter, a South Carolina secession flag was placed at the highest point on the University Building causing a town-wide uproar and outrage. That continued fear led to a rumor in the winter of 1861 that Confederates had raided Southern Indiana.

Units were hastily rallied from across Southern Indiana including one from Bloomington that had many students in it. Armed with squirrel rifles and a few pistols, they made it to Mitchell, Indiana before they found out that it was a false rumor. This foreshadowed the actions that took place during an actual Confederate Raid into Southern Indiana in 1863.

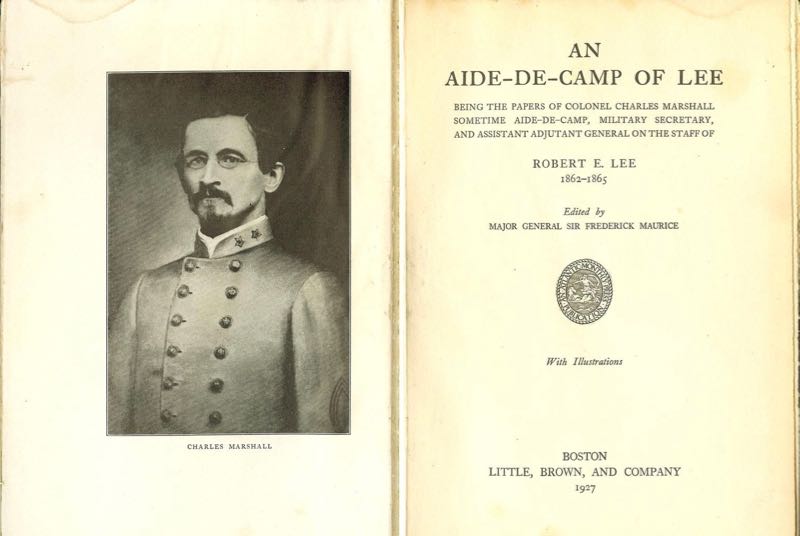

IU students, alumni, and faculty would serve on both sides in the Civil War; in all major campaigns; in all theaters including at sea; in ranks ranging from Private to General. They would include Brevet Brigadier General Theodore Read (Class of 1854), the last Union General killed in the war just days before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, and Colonel Charles Marshall (former faculty), who served as General Lee’s personal secretary.

1868-1874

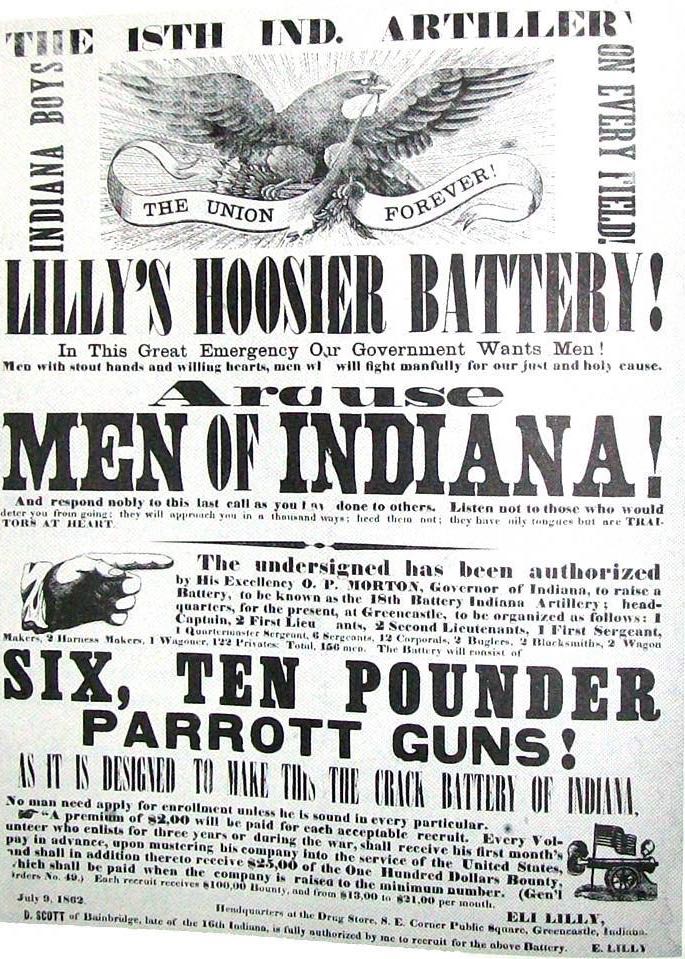

The Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 had created new opportunities for universities to teach agriculture, mechanical, and military science. This unfunded mandate put a new burden on a downsized Army to provide instructors to colleges.

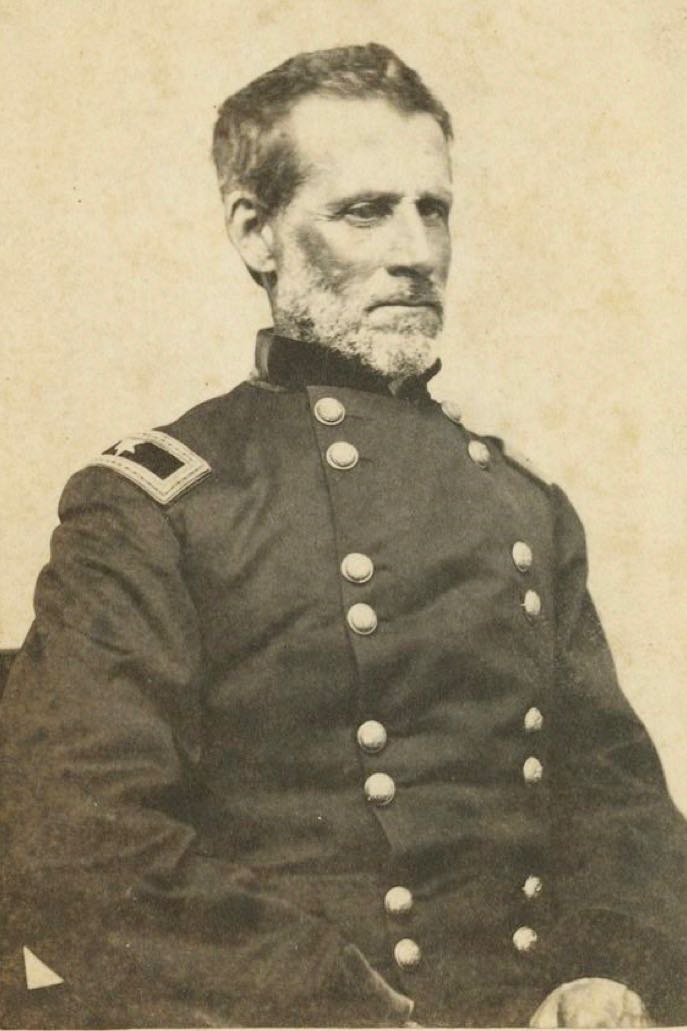

Although IU was the original recipient of the federal land grant, it was eventually shifted to Purdue University. However, IU was one of ten non land grant institutions that the Army decided to support with military science instructors. Most early instructors were new lieutenants right out of West Point. But IU was given the senior most instructor out of all of the Army’s military science instructors.

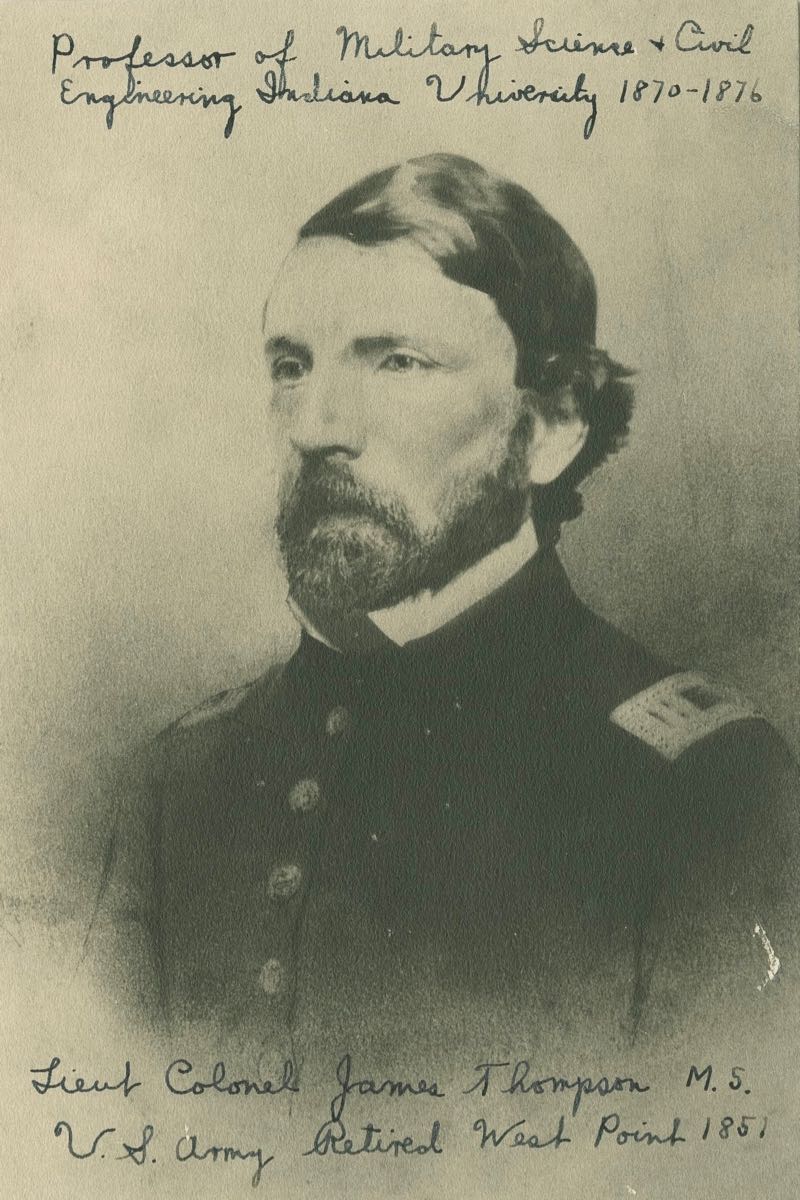

Initially, IU received Major General Eli Long. And the next year, they received Lieutenant Colonel James Thompson. LTC Thompson would teach military science and mathematics through 1874.

The students had slowly “voted with their feet” and chose not to sign up for the military science elective. Times had changed and most students no longer saw military science as fitting in the classical education curriculum.

Rather than leave the university, LTC Thompson retired from the Army and remained at IU as Professor of Mathematics for several years. His son John would attend IU for one year before being admitted to West Point. John Thompson would be a career soldier and retired in 1918 as a Brigadier General. He is best known as inventor of the Thompson Submachine Gun or “Tommy Gun.”

1916-1920

Military science once again became a topic of discussion on campus starting in the early 1900s. Two major federal actions made it easy for the university to start teaching military science again.

As the Mexican Border War heated up in 1916, the President of the United States called on National Guard units to mobilize. A Bloomington company formed that included many IU students and a few faculty members. By the summer of 1916, Company I of the 1st Indiana would be on duty down on the Mexican border.

That summer, Congress passed the National Defense Act of 1916, creating the Reserve Officer Training Corps. IU wasted no time seeking to have a unit stationed on campus and was one of the first of many to be approved. However, a shortage of available Army officers meant it would be the late spring of 1917 before the Army could send one.

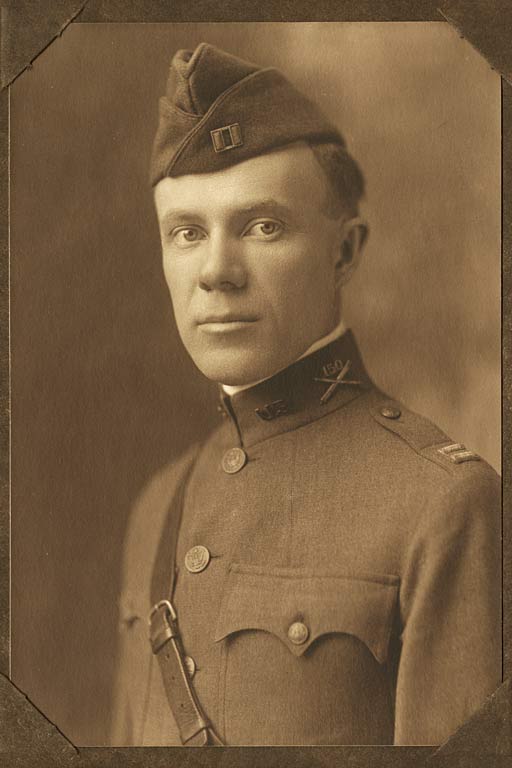

Not wanting to waste time, Kenneth “KP” Williams, Assistant Professor of Mathematics and a Lieutenant in the National Guard, became the “Founding Father” of ROTC (pictured on horse). He took charge of the program and started the first classes in February 1917. He was assisted by another young National Guard officer and IU graduate student Lewis B. Hershey. Hershey would go on to be a four-star General.

Following the model of other military science programs in 1917, IU made the course mandatory for all able-bodied freshmen and sophomore males, a policy that would remain in place through the fall of 1965. However, IU would unintentionally make a significant alteration to the program. – See IU Traditions & Blazing Trails

World War I

During World War I, the Bloomington campus of Indiana University became an Army training camp. A wartime program called the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) was implemented by the Army to slow the tide of enlistments and keep students in school for two or more years in case the war was long.

The majority of male IU students enlisted in the SATC. Fraternity houses were converted to barracks to accommodate the new soldiers. As the program was working with wartime urgency, no one stopped to consider that Indiana University was one of the few racially integrated college campuses in America.

As SATC units were assembled, African American students went into predominately white units just like they had been in the ROTC program. During the war, when the Army began allowing African American officers, many in the first class to be commissioned were IU alumni and students.

IU was one of the few places that SATC soldiers could study the new technology of the radio telegraph. Radio operation took a team of men and included how to fix the radio as well as how operate it. It took a truck to haul it and power it.

The IU Medical School was the first to see the war. Students from the Medical School formed an Ambulance Corps and were among the first units to Europe. They would later be followed by a team of faculty and students who formed an entire Army Field Hospital.

IU women saw limited opportunities overseas but some made it there as nurses and Red Cross or YMCA staff. Some served as Yeoman in the Navy, the first branch to open up non-nursing fields to women.

Many IU women became involved in a new type of service known as Medical Social Work and served in the Army as Reconstruction Aides. The women, known as ReAides, were responsible for helping soldiers recover from their injuries both mentally and physically.

Often times this was done through helping them learn new tasks or jobs that they would be able to do once they left the service. IU was a pioneer in this field. So much so that Professor Edna Henry, a recent PhD grad was loaned to the Surgeon General of the Army during the war. She was tasked with setting up a system for ReAide programs in all US Army hospitals.

Between the World Wars

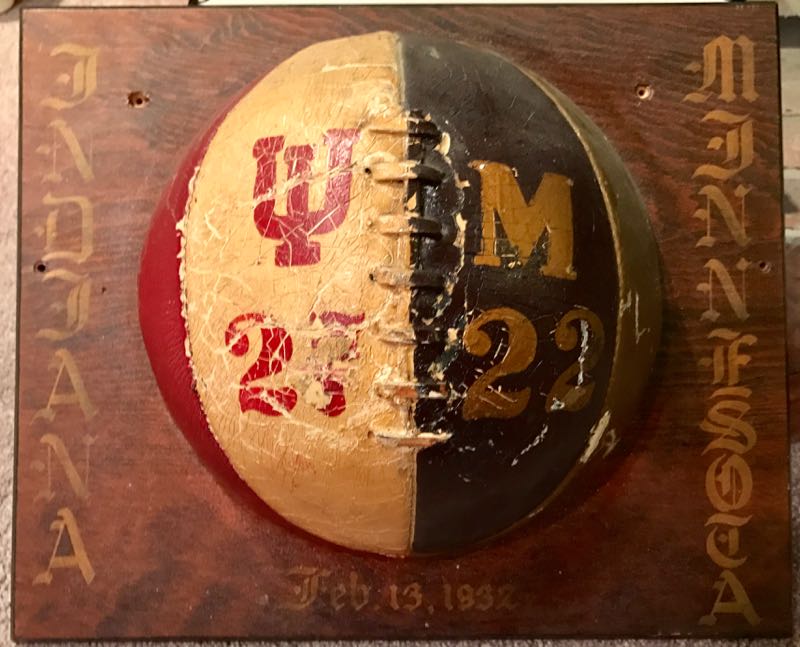

The post-WWI years brought some opposition to the ROTC program at I.U. A debate over the necessity of a compulsory ROTC program ensued in 1926. When put to a vote by students, the majority opposed the compulsory status of ROTC. However, because only 25% of the student body actually voted, the University Board decided the evidence was inconclusive, and no action was taken.

Throughout the rest of the 1920s, ROTC at I.U. continued to expand and increase its programs and offerings. In 1928 the I.U. ROTC formed their own company of the Pershing Rifles, a drill team for honor students, with 75 participants.

From the 1920s to the beginning of World War II in 1941, ROTC continued to flourish, and the Department of Military Science and Tactics struggled to find space to accommodate the growing number of students enrolled. This growth was due in large part to the course being compulsory for all incoming university male students.

World War II

World War II brought a period of growth and change for the Department of Military Science and Tactics.

Indiana University was much better prepared for World War II than World War I. Much of the campus leadership remembered the wartime campus of WWI. A War Council was formed and course work was condensed and a year-round schedule implemented. Indiana University offered not only its sons and daughters but also its faculty and facilities. And the military would use every bit of them.

In 1941 Colonel Raymond L. Shoemaker took over as Professor of Military Science and Tactics (PMST). He would later serve as Dean of Students at I.U. from 1946 to 1956. During Shoemaker’s tenure as head of ROTC, many new units and programs were established to enhance military training at I.U.

In 1942, the Quartermaster unit was formed to supplement the Infantry and Medical units. The Medical Administrative Corps was also organized to provide a future source of qualified medical officers to the armed forces and to prevent medical students from being drafted and depleting the number of qualified doctors on the home front.

The creation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACS) in the summer of 1942 heralded new times for the military and for ROTC at I.U. President Herman B Wells suggested an elective course on military training for women known as the Women’s Auxiliary Training Corps (WATC), whose mission would be to prepare women to work for the war effort after graduation, particularly in the public services sector of the armed forces.

The first of its kind, WATC had no official connection with the Army, but it replaced the physical education requirement for women at I.U. The program was discontinued after 1943 because the Department of Military Science and Tactics could not support it with the necessary faculty, staff and leadership.

The US Army via both the ROTC program and a new program called the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) became fixtures on campus. ASTP offered technical training to many who otherwise might not have considered college.

Unlike most ASTP schools though, IU’s technical training was not in engineering or sciences. Most of IU’s training was in foreign languages. This would begin a foreign language training relationship between IU and the military that continues to this day. ROTC, though smaller, would continue during the war including a strong contingent of students who joined the Army Air Corps.

The US Navy would also come to IU. The Navy saw IU’s School of Business as an excellent opportunity to train sailors and WAVES in the latest systems of logistics, procurement, accounting, and record keeping. Woman Marines and SPARS would come as well. The US Navy took over the Men’s Residence Center which held barely 600 men and crammed 1200 people into the main quad. They dubbed it the USS Indiana. It would continue to be known as “The Ship” well after the war until it was

re-named the Collins Living Learning Center.

During World War II, 9,200 I.U. alumni served their country. IU’s students and alumni would again go on to serve in every branch of service; in every theater of operations, and from Private to General.

Russell Church, IU Class of 1939, would be our first loss of the war. Church was stationed in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Days later, in one of the first attacks by Americans on the Japanese, he would be the flight leader’s wingman. His plane was badly damaged on its bombing/strafing run and was unable to pull up. The campus held a memorial services that included his family. Other names would soon follow including the beloved Ernie Pyle.

1960s

Challenges to mandatory ROTC programs began around country in the 1930s including at IU. The issues were campus militarization and required participation by Conscientious Objectors. By the early 1960s, ROTC was being challenged in new and broader ways regarding both the program curriculum and the academic credentials of the instructors.

The turbulent 1960’s brought even more changes for military instruction at I.U. The anti-war movement of the late 1960s had a significant impact on the ROTC program at Indiana University. Rallies in 1964, led by several student groups, including the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), protested the mandatory enrollment of all male freshmen students in ROTC. The students claimed victory when in October 1964 Public Law 88-647, also known as the Reserve Officers Training Corps Vitalization Act, was passed.

In December 1964, due to pressure from the Student Senate, anti-ROTC protestors, and others who argued against a compulsory course, I.U. administrators decided that for the first time in almost 50 years ROTC should be optional. This lead to a drop in enrollment in ROTC by 60%, but the program remained at the university thanks in part to President Herman B Wells and university administrators who decided that I.U. needed to offer a choice to Indiana college students who wanted to enroll in ROTC.

In April 1969 radical student groups attempted to burn the ROTC building down. These sentiments eventually culminated into a series of large anti-ROTC protests from 1969-1970. These protests called for the university to, among many other things, drop the ROTC program completely and rid the campus of any military presence. When the request was to put to a vote by the student body, however, the majority opposed abolishing the ROTC, and the program remained intact.

IU Traditions & Army ROTC

Some of biggest and most historic traditions of Indiana University have ties to the ROTC program.

The Marching Hundred

The IU Band became the ROTC Band during the early days. ROTC provided the band uniforms and official university sanction (all the freshmen and sophomores had to be in ROTC anyway). During this time they earned their moniker of “The Marching Hundred.” After WWII they would leave ROTC and become part of the Department of Bands in the Jacobs School of Music.

The Little 500

The Little 500 bicycle race also has military connections. In 1950, Howdy Wilcox, a member of the IU Foundation board, saw students who were likely WWII veterans and ROTC cadets racing bicycles around a residence hall. Howdy’s father had been an Indy 500 driver so the idea for Little 500 was born. Howdy was himself an alum of the IU ROTC program. He served in WWII where he received the Silver Star. He later retired from the Indiana National Guard as a Major General. Howdy is one of the 25 Generals and Admirals known to have connections to IU.

Blazing The Trail

Women in ROTC

In 1966 the Army and Air Force decided to allow women to take ROTC course work. And in 1970, IU became one of only ten institutions that were allowed to commission women officers. Fifty years of slow integration had paid off.

Racially Integrated University & ROTC

Being one of the few racially integrated universities and the only one with a mandatory ROTC program, IU created racially integrated units. This was a year before the Army would begin allowing African Americans to be officers and nearly fifty years before racial integration of the Army except for the wartime SATC program.

Following World War I in 1920, IU culture would again impact the program and allow limited roles for women who wished to participate. Over time, those roles would come to include uniforms, “equivalent” cadet ranks (later just referred to as cadet ranks), and a broad spectrum of responsibilities.

The Golden Book

In the 1890s during the Spanish American War, the Indiana Daily Student began publishing and maintaining a list of students currently serving in the military. This led to a desire to make a list of all IU alumni who had served in the Civil War.

When WWI began, the Registrar and the Alumni Association took responsibility for tracking students and faculty who left to serve in the war. After the war, several rounds of mailings were sent to collect as much information as possible about Alumni service.

In 1932, as part of the Memorial Campaign, these names were enshrined in a permanent book known as The Golden Book. The book listed all the “Sons and Daughters of Indiana University who have fought in the wars of the Republic” with special notes about those who had died in service and was put on display in the Indiana Memorial Union.

When WWII came the book filled quickly. The post war rush left the project shelved for many years. In 2011, the university began digitizing the book and collecting the names of those who have served since WWII.

Indiana University

Army ROTC

814 E. Third Street

Bloomington, IN 47405

(812) 855-7682

Indiana University

Army ROTC

814 E. Third Street

Bloomington, IN 47405

(812) 855-7682